I don’t like metroidvanias, at least, that’s the lie I tell myself. The backtracking, the slow discovery and unlocks. I pretend that those mechanics frustrate me when in reality there’s a dopamine hit knowing you can explore that hidden away area and finally reveal the treasures within. I should face facts, I mean Hollow Knight and Dead Cells both sit in my top game lists. I could write video essays about how Ori scarred me emotionally. Maybe it’s time I embrace it? Ease into it with something light… Maybe a game focused on the duality of life and death, and how grief is a personal journey we all must take so that from an ending, a beginning is found? Nice and light…

There’s a lot going on in Tales of Kinzera: Zau, and heavy themes are stacked up on each other like Jenga bricks, which is why it’s so impressive to me that at no point in my 9 hours, did the game fumble them once.

A warning before we truly get into this, we’re going to be discussing some heavy themes as death and personal grief are the wheels on which this bike rides. If at any point the discussion gets too much, just walk away and come back if or when you are ready.

Familial bonds and grief aren’t exactly new in games. Games like God of War give you a Father and Son journey of mythical proportions. While The Last of Us hits you with grief and loss right from the jump.I don’t think I’ve ever played a game that was built on loss though. The only other title I can think that exists in that space would be That Dragon, Cancer, and that’s a different beast entirely. It also came out during a time when I wasn’t in the right headspace to deal with talking about cancer. Tales of Kinzera: Zau was built as an ode to Abubakar Salim’s father, to create a way to deal with his grief, and make a game true to him and his Father. Video games aren’t just made overnight, so there’s an impressive strength in potentially extending your grief by using it as the source for a game. Using game design as catharsis would be one thing, but to swim in loss and use it as a core ideal for a game? I’m not sure I have a strong enough character for that. What’s even more impressive though, is taking that grief and honing it in such a way that you create a story that is truly beautiful from it. That’s what Tales of Kinzera: Zau is. Beautiful, from start to finish.

When Tales of Kenzera: Zau was shown off at The Game Awards 2023, Abubakar came out on stage and told us the background behind why he made the Tales of Kenzera: Zau. I was expecting the game that was about to be shown to be a walking simulator, or a Telltale style story game. Instead what we were shown was a colourful, fast paced Metroidvania, it caught me by surprise, it showed the trappings of a game that wasn’t aiming to make a game devoted to death, but instead devoted to life. A game that used death, and grief as a backdrop to tell a meaningful story.

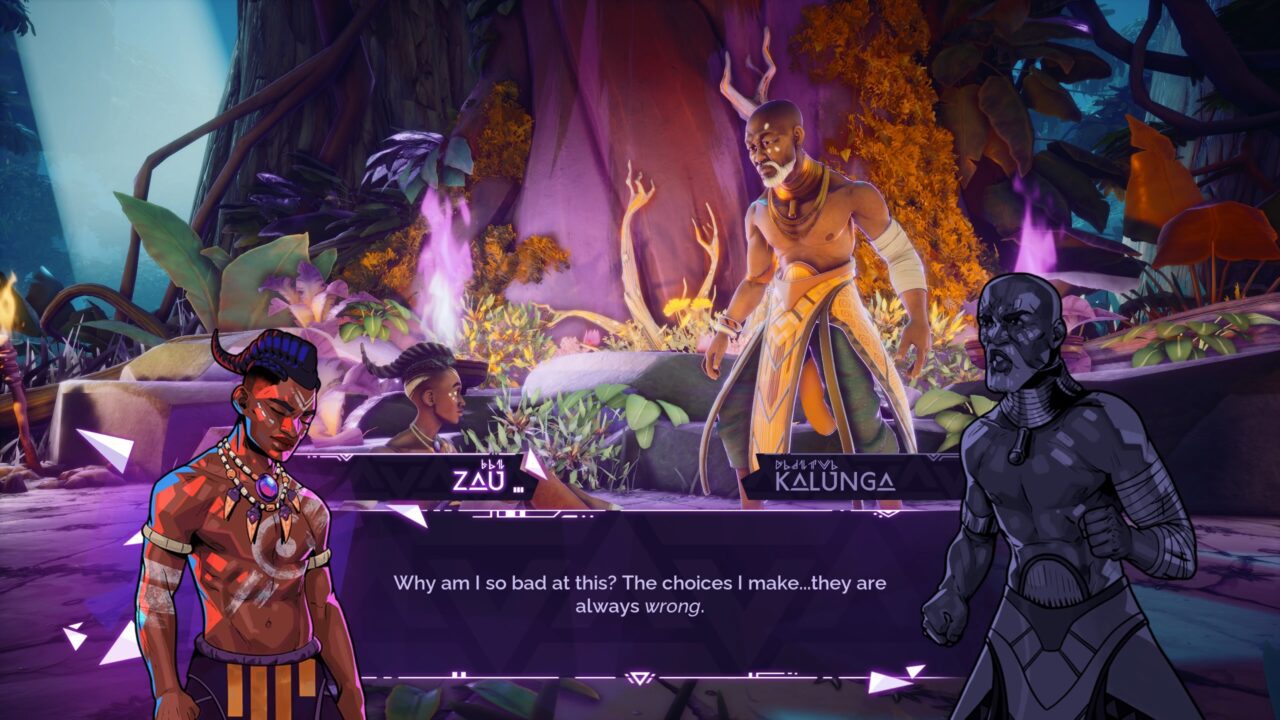

Tales of Kenzera: Zau starts off with the death of a Father, and a gift for their son. Zuberi is dealing with the loss of his father, and is given a book his Father left for him in the days after. Within those pages our story lies. Zau, Shaman to the people of Amandla beseeches Kalunga the God of Death, to return his Father’s spirit, in exchange Zau will shepard the 3 great spirits who have denied Kalunga into the realm of death. To aid him in this journey, Zau is equipped with two masks. The mask of the Moon, a mask focused on ranged attacks and freezing stasis, and the mask of the Sun, a close range combo mask. The game gives you free reign to swap between them as needed during combat which can set up some very satisfying combinations. Duality. That’s the name of the game, and it’s a theme that keeps appearing throughout. Fathers and sons. Life and death. The two masks, and more that I can’t get into for spoiler reasons. Just like the way you can flow gracefully between the two masks during combat, these heavier themes like duality and grief are never heavy handed, dancing gracefully in and out of focus during the story. It’s this delicate touch that makes the story of Tales of Kenzera: Zau shine. It would be easy to be overly heavy handed when discussing death. Especially when it’s at the core of the main objective of the game it could be heavy handed by accident, but Tales of Kenzera: Zau not only uses the stages of grief in a way that feels real, it sticks the landing and the payoff feels earned.

Zau as a character, feels relatable, a Son doing everything he can to reclaim more time with his Father. Headstrong and defiant from the start, negotiating with the god of death, that denial that can be so strong when met with something as world changing as losing a relative. There’s a moment when Zau proclaims “The choices I make… they are always wrong”, that self defeatism, helplessness at not knowing how to fix the situation spoke so true to me that I’m still thinking about it.

The world design also shares this idea of traumatized beauty. A vibrant world of colour trying to shine through underneath the anguish. We’re shown villages beset by storms, poison that has seeped into the land ruining lush water. Deserts that have a majesty to them underneath a struggling volcano that no longer lies dormant. All of this is then backed up with a soundtrack that brings the world to life. The voice acting also deserves a mention, with a great supporting cast and Abubakar himself playing Zau, making each character shine.

Unfortunately that theme of duality also extends to the story and the gameplay. There’s gameplay aspects in Tales of Kenzera: Zau that seem either neglected due to focusing on more important moments like the story, or just feel like they slipped down the priority list and didn’t get addressed before that ever looming launch window. Most importantly. The Map. I may be spoiled by having recently played Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown, but the map in Tales of Kenzera: Zau leaves a lot to be desired. I mean ok, if you want to get technical, yes it is a map, and yes, it does allow you to get from point A to point B, it shows you your objective and other markers. Those extra quality of life features you’re looking for in a metroidvania are missing though. You’re unable to place markers or waypoints on the map, and discovering an area uncovers more of the map than you’d like, making it harder to discern between where you’re been and where you were locked out of until after you picked up a new shaman power. It’s not as frustrating as it could be as the map layout is a little too streamlined in places, most of the time, paths either loop back on themselves, or are split in two directions with one being the right one, and the other being the bonus. There are rooms tucked away scattered around but that depth and discovery that you seek in a metroidvania isn’t as strong here as you’d want it to be.

Which is a shame as the rest of the gameplay is satisfying enough. Combat allows you to pick a playstyle that works for you and builds upon it. Whether that’s mainly focusing on one singular mask, or weaving the styles of both of them together. Trinkets found throughout the world work as you’d expect them to in a metroidvania. Items you can equip into a number of slots that give you minor alterations in your damage or spirit collection. Further trinket slots can be unlocked from completing Shaman Trials, as well as increasing your spirit bar, which allows for more healing opportunities or uses of your super abilities. There’s also some rather simple upgrade trees for the two masks, and as would be expected from a metroidvania additional powers that you’ll unlock as you progress that allow you to access areas of the world once locked off. It all builds out an enjoyable combat system, one that’s not needlessly deep, but feels crafted for the world, like the two mask system, finding the correct balance between depth and requirement. Thanks to new enemies being added throughout the game rather than just different coloured enemies, the combat also manages to remain enjoyable throughout. The combat trials you can encounter to get your upgrades can also be challenging at points.

Outside of the map the only frustration I encountered was a minor one regarding gauntlets, and thankfully those were limited. At several points during the game you’ll be required to Crash Bandicoot style, flee for your life. Failure resets you back to the beginning of the gauntlet, this is an all or nothing style affair. Thankfully, like I mentioned they are limited, and only a few of them exist, as they can be especially aggravating if you keep getting to the end and just bounce off the door you’re meant to explode through for over 30 minutes… Not that it happened to me of course.

Those minor missteps with the map system and save checkpoints still aren’t enough to detract from what Tales of Kenzera: Zau is trying to accomplish though. It may not reach the lofty heights of something like Hollow Knight or Ori and the Blind Forest but for a first attempt, and for a game coming from the place that it did, Tales of Kenzera: Zau manages to achieve a clean and impressive result. Tell an engaging story from start to finish, and I have nothing but respect for Abubakar Salim for taking his grief and channeling it into such a beautiful story that both his father and him should be proud of.